|

|

|

| |

||

Emancipation Proclamation and the Little People's Petition

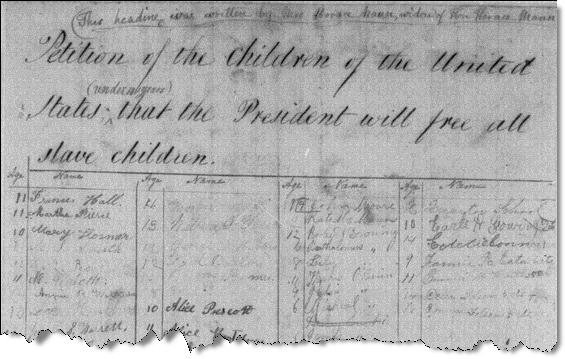

The moment when students learn that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free all the slaves is sobering. For some, the revelation leads to further enlightenment as they seek to learn more about Constitutional history. But for others, the revelation throws them headlong into the canyon of cynicism. They emerge carrying a burden of bitterness, claiming that a racist Lincoln did the safe thing by, in fact, freeing no one with his proclamation. Students in 1864 wrestled with these same questions: Had Abraham Lincoln done enough? Could he do more? Teacher Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, widow of the great educational reformer Horace Mann, sent a petition to Senator Charles Sumner from the children of Concord, Massachusetts, for delivery to Lincoln. Across the top she boldly inscribed: "Petition of the children of the United States; (under 18 years) that the President will free all slave children." One hundred and ninety-five students had signed the petition. (Parents added their own annotations.) Lincoln labeled the envelope that contained the petition, "Little People's Petition."

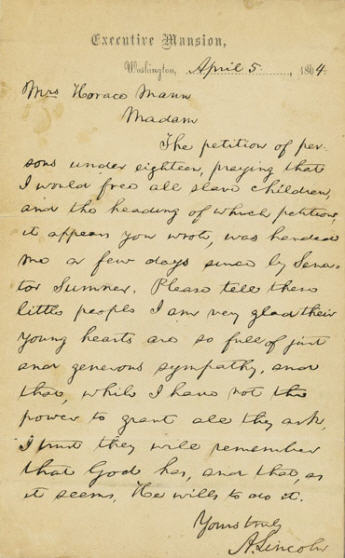

Lincoln was well aware that his proclamation did not free all the slaves. He was also quite clear on the fact that the Constitution protected slavery where it existed--even before the Supreme Court essentially declared that the federal government could do nothing to stop slavery from spreading anywhere it well pleased to go. Lincoln called out the Emancipation Proclamation as a "fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion," and executed the proclamation by "virtue of the power vested in me as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and Government of the United States." With that authority, he declared all slaves held in any State or part of a State that was in rebellion against the United States to be free. The students--like Lincoln, no doubt--wanted all the slave children to be free and petitioned the President to make it so. To this, Lincoln forwarded the following letter in reply to their teacher:

(The letter was forwarded through Senator Sumner, to whom Lincoln wrote: "If Senator Sumner thinks it would be proper, he may forward the inclosed to Mrs. Mann.") This letter has come to be known as the Little People Letter. Sotheby's called it Lincoln's most personal and powerful statement on God, slavery and emancipation. On April 3, 2009, the letter was sold at auction by Sotheby's New York for $3.4 million. (A draft copy of the Little People Letter is held by the Library of Congress.)

The description of the letter and its condition was provided by Sotheby's: "Autograph letter signed ("A. Lincoln"), 1 page (8 x 5 in.; 204 x 126 mm) on a bifolium of Executive Mansion letterhead. ...Browned, fold separations neatly mended, verso of integral blank stained as though from mounting, integral blank with some marginal restoration." In reply to Lincoln's letter on April 20, Mrs. Mann wrote:

Lincoln's reply was widely reprinted and lithographed. Roy Basler notes that because Mrs. Mann wished to remain anonymous, the facsimiles show "Mrs. _____ (of Concord Mass.)" rather than the "Mrs. Horace Mann" address from the actual letter. sources: Basler, Roy P. (editor). The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, volume VII, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953, p. 287, 288. Sotheby's. Presidential and Other American Manuscripts from the Dr. Robert Small Trust. Lot 85, Lincoln, Abraham, as Sixteenth President.

|

|

Copyright © 2005-2016 Alta Omnimedia. All Rights Reserved.