Hannibal Hamlin:

Lincoln's Vice President

Hannibal Hamlin was born in the same year Lincoln was born, in Maine, nearly 1200 miles from Lincoln's Kentucky home. Like Lincoln, Hamlin was a surveyor for a time and was a lawyer prior to entering politics. Hamlin started as a representative in his home state of Maine. He was elected in 1848, to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate, the same year Lincoln served his only term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Hamlin's political career began as a Democrat, though he was well known to oppose the extension of slavery and favored the Wilmot Proviso. In 1854, he opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise. Democratic President James K. Polk wrote in his diary, "Mr. Hamlin professes to be a democrat, but has given indications during the present session that he is dissatisfied, and is pursuing a mischievous course . . . on the slavery question." When the Democratic National Convention two years later endorsed that repeal, Hamlin left the Democratic party in disgust. His defection to the recently-organized Republican party was a much talked about event.

The Republicans nominated Hannibal Hamlin for Governor of Maine in 1856. Hamlin did not want to be Governor but after Republicans made it clear that he would not likely return to the U.S. Senate, Hamlin made an agreement with the them to run if he could then return to the Senate. Hamlin defeated both the Whigs and the Democrats and won the Governorship, becoming the first Republican governor of the state--a major boon for the Republican party. But Hamlin only served as Governor in January and February 1857, resigning at the end of February to return to the Senate for his third term. He loved serving as a Senator.

CDV of Hannibal Hamlin (1860s)

back carries imprint: Published by E. Anthony,

501 Broadway, New York. From Photographic Negative,

From Brady's National Portrait Gallery

Hannibal Hamlin was nominated to run on the Republican ticket as Vice President in 1860. The party chose him because he was against slavery and being from Maine, he would help bring in votes from the Northeast to balance the ticket. This came as a surprise to Hamlin, who learned of his nomination while playing cards in Maine. He did not want the nomination but was told that his decline of it would only give ammunition to the Democrats. Explaining in a letter to his wife, Hamlin said, "I neither expected or desired it. But it has been made and as a faithful man to the cause [of limiting slavery], it leaves me no alternative but to accept it."

Lincoln Introduces Himself to Hamlin

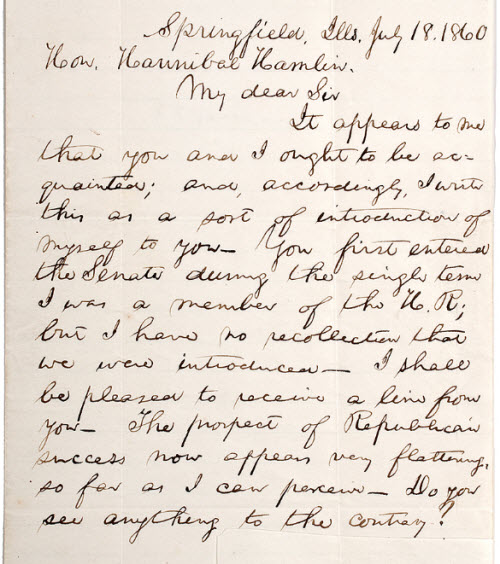

A few weeks after the Republican convention in 1860, Abraham Lincoln wrote to Hannibal Hamlin to introduce himself.

Springfield, Ills, July 18, 1860

Hon. Hannibal Hamlin.

My dear Sir

It appears to me that you and I ought to be acquainted; and, accordingly, I write this as a sort of introduction of myself to you. You first entered the Senate during the single term I was a member of the H.R; but I have no recollection that we were introduced. I shall be pleased to receive a line from you. The prospect of Republican success now appears very flattering, so far as I can perceive. Do you see anything to the contrary?

Note that Lincoln's signature has been clipped from this letter, which otherwise appears in his handwriting. This letter is listed as lot 110 in Cowan's Auctions American History catalog for the December 7, 2012, auction. It is estimated at $25,000-$30,000.

Abraham and Hannibal in 1860

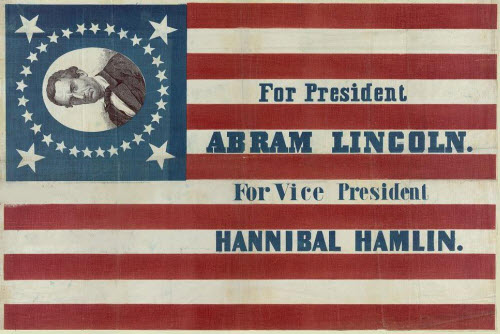

Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin ran on a platform of preserving the Union and stopping the spread of slavery. This campaign poster, for example, exhorts voters to vote for free speech, free homes, and free territory. "The Union must and shall be preserved."

They also stood for the protection of American industry. Note the factory smoke stacks and the merchant ships between the two portraits. Lincoln was friendly to railroads and other corporations and favored expanding an infrastructure that would promote interstate commerce.

This 1860 campaign flag was meant to hang vertically so that Lincoln's face would be properly oriented. Abram and not Abraham? Yes, the printer took the liberty of making a change to Lincoln's name so that it would better fit the flag design.

The Lincoln-Hamlin campaign also played on the name of Abraham Lincoln, reconfiguring it as AbraHamlinColn or Abra/hamLin/coln.

The reverse side of a popular Lincoln-Hamlin campaign ferrotype showed Hamlin:

Hannibal Hamlin, the First Republican Vice President

In 1861, Lincoln became the first Republican President and naturally, Hannibal Hamlin became the country's first Republican Vice President.

Through the process of the Electoral College, state elections determine each state's electors. You actually vote for the candidate's electors, not the candidates themselves. The Governor of each state sends a certificate to Congress indicating the electors for that state based on the popular vote in the state. (For more about this process and the 1860 election, see How We Elected Lincoln, by Abram J. Dittenhoeffer, a campaigner for Lincoln in 1860

and a Lincoln elector in 1864.) The winning electors cast their votes for President and Vice President on separate ballots.

These electoral votes are counted in a joint session of Congress. As President of the Senate, the Vice President presides over the vote and announces the winner for President and the winner for Vice President.

Note that in the event of a tie in the elector's votes, the House of Representatives would vote and determine the President, and the Senate would vote and determine the Vice President. (This, incidentally, is why it does not make sense to argue that the Republicans stole the election in 2000. The Governor in Florida, Jeb Bush, had already sent the certificate to Congress indicating that George W. Bush's electors would be representing the state. Had Al Gore not brought suit and therefore not brought the Courts into the matter, Bush's electors would have voted for Bush and Bush would have won. And in the event of a tie, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives would have voted for George W. Bush as President, and the Democrat-controlled Senate would have likely voted for the Democratic Vice Presidential candidate, Al Gore's running mate: Joe Lieberman. As President of the Senate (because he was Vice President under Bill Clinton), Gore would have announced Bush as the Presidential winner and Lieberman as VP winner of the election.)

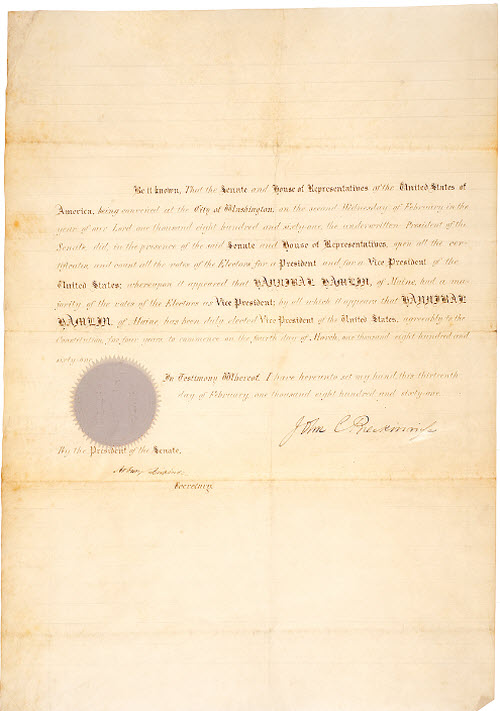

In 1861, after counting the electoral votes, President of the Senate John C. Breckinridge (Vice President under James Buchanan) announced the two winners of the 1860 election: Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin. This is the paper he issued certifying Hamlin as the VP winner.

This certification is not on any sort of official letterhead--it's simply centered on a 16" x 22" piece of ruled vellum. However, it is sealed with a "large white seal affixed lower left, featuring three classical feminine figures with eagle overhead," according to the description by Cowan's Auctions (it is lot 112 in the December 7, 2012, American History auction, estimated at $5000-$7000).

Be it known, That the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of America, being convened at the City of Washington, on the second Wednesday of February, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one, the underwritten President of the Senate, did, in the presence of the said Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates, and count all the votes of the Electors for a President and for a Vice-President of the United States; whereupon it appeared that Hannibal Hamlin, of Maine, had a majority of votes of the Electors as Vice President of the United States, agreeably to the Constitution, for four years, to commence on the fourth day of March, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one.

In Testimony Whereof, I have hereunto set my hand this thirteenth day of February one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one.

John C. Breckinridge

The certificate is signed by John C. Breckinridge, President of the Senate, and Asbury Dickins, Secretary.

Hamlin Bored as Veep but Served Again

Hannibal Hamlin had little role to play as Vice President. The etiquette of the day meant that Hamlin could not attend most Cabinet meetings. If he thought the Governorship was boring compared to being in the Senate, the Vice Presidency must have been a real snoozer. Hamlin, in fact, described it as a "nullity." He later explained to an interviewer:

There is a popular impression that the Vice President is in reality the second officer of the government not only in rank but in power and influence. This is a mistake. In the early days of the republic he was in some sort an heir apparent to the Presidency. But that is changed. He presides over the Senate--he has a casting vote in case of a tie--and he appoints his own private secretary. But this gives him no power to wield and no influence to exert.

Consequently, Hamlin spent most of his time in Maine, rarely visiting the White House. Surely Mary Lincoln encouraged this, since it was said that she and Hamlin disliked each other.

Hamlin had a cordial relationship with Abraham Lincoln and did occasionally have Lincoln's ear. He was instrumental in getting a New England representative onto Lincoln's Cabinet: Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy. He also urged Lincoln to pursue emancipation in 1861, and encouraged him to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

Though he loved being a Senator and rarely missed a day when the Senate was in session, Hamlin did not like serving as President of the Senate, so he frequently was absent. Likely the only thing he considered a real service during this period was his serving in the Union Army in 1864. When the war began in

1861, Hamlin had enlisted as a private in the Maine Coast Guard. His unit was called to active duty in 1864. As Vice President, he could have accepted a purely honorary place

in the unit but he insisted on active duty, saying "I am the Vice-President of the United States, but I am also a private

citizen, and as an enlisted member of your company, I am bound to do my duty." He served along side enlisted men and drilled and stood at guard duty until his tour of duty ended in September.

If 1864 was a highlight for service, it was also a lowlight. In June 1864, Hamlin expected to be nominated to appear on the Republican ticket with Lincoln for re-election. But Maine was going to go to the Republicans even without Hamlin, so a Southerner was chosen to balance the ticket: War Democrat Andrew Johnson, who had proven to be a good war Governor of occupied Tennessee. Hamlin was surprised and disappointed. Trying to console Hamlin, Secretary of the Senate John W. Forney wrote, "To be Vice President is clearly not to be anything more than a reflected greatness. You know how it is with the Prince of Wales or the Heir Apparent. He is waiting for somebody to die, and that is all of it."

Hamlin's term expired on March 4, 1865. Just six weeks later, Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson became President. (Hamlin's son and daughter, Charles and Sarah, were at Ford's Theater on the night of Lincoln's assassination.) How different reconstruction would have been with Hamlin as president rather than Southerner Andrew Johnson!

Hannibal Hamlin returned to the Senate in 1868, to serve two more terms, declining to run again in 1880, because of heart problems. His last act of public service was as Ambassador to Spain under President James A. Garfield (the second U.S. President to be assassinated). From 1887 to 1889, Hamlin was the only living former Vice President, having outlived all of his successors. Hannibal Hamlin collapsed while playing cards in Bangor, Maine on July 4, 1891, and died that evening at the age of 81.

Here are some biographies of Hannibal Hamlin including one by his grandson, Charles Eugene Hamlin (The Life and Times of Hannibal Hamlin):

author of this article: Renee Gentry

source(s):

"Hannibal Hamlin, 15th Vice President (1861-1865)," United States Senate, http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Hannibal_Hamlin.htm