|

|

|

| |

||

Tad Lincolnaudio available in podcast episode 3 Abraham Lincoln's Fourth and Youngest SonTad Lincoln was born in Springfield, Illinois, on April 4, 1853. He was named Thomas Lincoln after his paternal grandfather, with no middle name or initial. It was Abraham Lincoln who gave him the nickname "Taddie," because as a baby, the boy had a rather large head and that reminded Lincoln of a tadpole. When Taddie got older, Lincoln took to calling him Tad, but Mary Lincoln called him Taddie for his entire life. Tad had a speech impediment, and likely had a learning disability. This seemed to endear him to his parents all the more. Tad didnít live under many rules at all, at least up until the time he left the White House. In an age where children were to be seen and not heard, Lincolnís parental philosophy was "kids will be kids." We know that Abraham Lincoln's law partner, William Herndon, frequently complained about the havoc the Lincoln boys would wreak when they visited the law office. Herndon called the Lincoln boys "the little devils." Lincoln was usually amused by their shenanigans and frequently egged them on. He seemed oblivious to what we would say was chaos--letting the boys take their ponies and goats inside the White House, for example. And, clearly, he did not appreciate anyone reprimanding his children. Tad at the Telegraph OfficeA story is told of a time that Tad accompanied Lincoln to the telegraph office in Washington. While Lincoln was looking over some dispatches, Tad went into the other room and busied himself by drawing on a very white marble tabletop with some very black ink. Madison Buell, the telegraph operator, grabbed Tad by the collar and dragged him into the room where Lincoln was reading. Buell was outraged and told the President that Tad had ruined the table. Tad, in his typical honesty, held up his black fingers to show that he had, in fact, been up to some fun. At that, Lincoln lifted Tad up into his arms and said, "Come, Tad; Buell is abusing you." Tad and Willie and JackTad was close to his brother Willie, who was two years older. Willie was Tad's accomplice in a great many pranks and, in general, was a very close playmate. When they moved into the White House, Tad was just about to turn eight, and Willie was ten. This little story from a wonderful book by Ruth Painter Randall (Lincoln's Sons

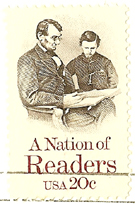

The Famous Father-Son PortraitWithin a year after moving into the White House, Willie died. This drew Tad all the closer to the Lincolns and made them all the more lenient with him. Tad surely was the little devil Herdon said he was, and yet, he obviously had his endearing moments. One of those moments was captured in the Brady studio and the picture has since become one of the most popular father-son portraits ever. Iím sure youíre quite familiar with the picture, which was taken in February, 1864. Lincoln is seated and Tad is standing at his side. They are both reviewing a book.

The U.S. Postal Service used this picture on the 20 cent stamp issued October 16, 1984, †titled, "A Nation of Readers."

Topps, the famous baseball card manufacturer, encased the U.S. postage stamp in its 2009 American Heritage stamp series. One little note of trivia: This picture is the only portrait of Abraham Lincoln which portrays him wearing glasses. Robert Lincoln, the oldest Lincoln son and Tad's senior by nine years, said that while his father was in Matthew Brady's studio:

Lincoln Lore (issue 392) relates that the album "belonged to Brady and was available to his patrons while they were waiting for their appointments. It was a sort of'ĎWho's Who' in pictures, and among the interesting portraits it contained were some of P. T. Barnum's celebrities who helped to make the early showman famous. Brady is known to have taken photographs of Mr. and Mrs. Tom Thumb, The Siames Twins, ...The Fat Lady, The Human Skeleton, and many others." Tad Receives a Formal EducationTragically, Tad's beloved father was murdered just 10 days after Tad's twelth birthday. Now Tad was the only one living with Mary in whom she could take comfort. She mentioned him in a letter in November, 1865, saying, "I press the poor little fellow closer, if possible, to my heart, in memory of his sainted father, who loved him so very dearly." Though Willie had been put under the supervision of a tutor, Tad had received no primary education at all. He had always just been left to play and enjoy himself. In the fall of 1865, Mary enrolled Tad in a school in Racine, Wisconsin. That November, she wrote to Frances Carpenter--the painter who had lived at the White House while he painted his masterpiece depicting Lincoln sharing the Emancipation Proclamation with his cabinet--that "Taddie is learning to be as delighted in his studies as he used to be at play in the W.H. (White House). He appears to be making up for the great amount of time he lost in W (Washington)." After that, he was put into a public school. But since it was very unlikely that at that time he could read--despite the fact that he was 13 years old--and because he was big for his age, he probably had a hard time in school. Remember, he still had his speech impediment. No matter the era, kids are kids, and if you're different, you're going to be made fun of. Tad was not exempt from that: The kids at school called Tad "Stuttering Tad." In 1868, Robert Lincoln--who was about 25 years old at the time--consulted with some specialists about Tad's speech impediment and some improvement was made. In the summer of that year, Mary made plans to move to Europe, where she thought Tad could receive an education at a cheaper expense. As you may know, Mary was not taken care of by the government in the way in which our former First Families are now. It was at this time, in fact, that Congress was debating about finanical support for her, so you can imagine that they didnít look very highly at all on her plans to educate Tad in Europe. Nonetheless, Mary and Tad set sail for Germany in October. In Germany, Tad's learnings accelerated more than at any other time in his life. In March of 1870, Mary wrote to Robert's wife that "Taddie is doubtless greatly improving in his studies." By October of that year, they moved to England, where Tad was with a tutor seven hours a day. Tad Lincoln Dies at 18Mary became quite ill early in 1871, and Tad himself was showing signs of illness as well, so they returned to Chicago. Mary improved, but Tad gradually became weaker, and on July 15, 1871, he died. The Chicago Tribune published an account of Tadís death the next day. It said, in part:

Tad was just 18 years old when he died. You can imagine that following the death of her 4-year old son Eddy, her son Willie, her beloved husband President Lincoln, and Tad, Mary Lincoln began a steady emotional and mental decline.

author of this article: Renee Gentry sources: Lincoln Lore, issues 193, 244, 392. Randall, Ruth Painter. Lincoln's Sons, Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1955. Whipple, Wayne. The Story-Life of Lincoln, Memorial Edition, Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co., 1908.

|

|

Copyright © 2005-2015 Alta Omnimedia. All Rights Reserved.